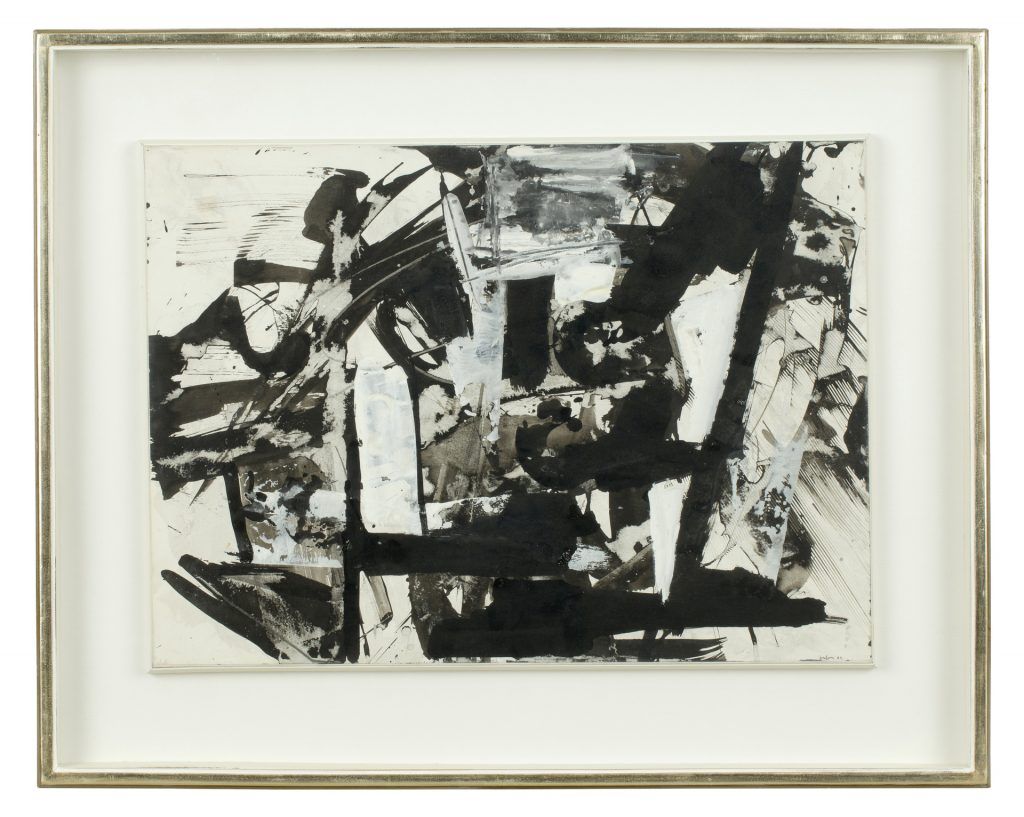

Emilo VEDOVA

Italy, 1964

Acrylic on paper laid on canvas, 42 x 58.50 cm

signed and dated (lower right)

Emilo Vedova was an exponent of Italian artistic life in the second half of the 20th century. He was part of the generation that wished to fill the cultural void created by twenty years of Fascist rule through socially committed artistic activity, which involved active participation in political and civic life. During the Second World War, Vedova participated in the Italian resistance movement, recording his experiences in the partisan drawings. He also joined Corrente (1942–1943), the anti-Fascist association that also included Renato Birolli, Renato Guttuso, Ennio Morlotti, and Umberto Vittorini. Their manifesto proclaimed ‘the revolutionary function of painting ... With our painting, we are going to hoist flags’.

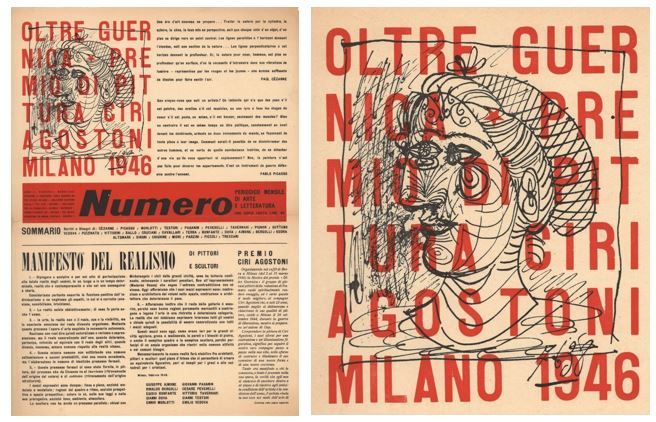

In 1946, Vedova collaborated with Morlotti on the Manifesto of Realism of Painters and Sculptors (Oltre Guernica). Despite its name, this manifesto is not overwhelmingly concerned with visual style or language. Instead, taking a cue from the famous 1937 painting by Pablo Picasso, the document emphasizes painting as an act of participation and political engagement. Artworks by Vedova, such as The World on its Tiptoes (1946), The Struggle (1949) and Concentration Camp (People and Barbed Wire) (1950) exemplify the imagery which clearly followed the principles of the manifesto. During this period, he began his Geometrie nere (Black Geometries) series, black and white paintings influenced by Cubist spatiality. These black geometries express the anxiety and anguish of the period.

Vedova was also a founding member of the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti in Venice, simultaneously active in Milan and Rome, until its dissolution in 1952. In the same year, he joined Gruppo degli Otto, where he developed a colourful and gestural visual language, increasingly informed by French Art Informel, Tachism, and American ‘Action painting’, creating dynamic spatial structures that enabled him to express the intense feelings and ethical-social commitment engendered by the Second World War.

Photo: Alberto Grifi, Rome

Vedova was awarded the Grand Prize for Painting at the 1960 Venice Biennale. The same year he created moving light sets and costumes for Italian composer Luigi Nono’s opera Intolleranza ’60. This experience led to the first Plurimi in 1961–63: freestanding, hinged, and painted sculpture/paintings made of wood and metal. From 1963 to 1965, Vedova worked in Berlin, at the Deutsche Akademischer Austausch Dienst. By invitation of the Ford Foundation for their artist-in-residence program, just two years after the construction of the wall in 1961, he created his best known Plurimi, the Absurdes Berliner Tagebuch ‘64, presented at the Documenta III, Kassel.

Photo: Elizabeth Pfefferkorn, Berlin

Experimenting with the expansion of the classical pictorial space, Plurimi are colossal assemblage of jagged wooden pieces painted in clashing colours, which convey the trauma of the divided city. Hung from the ceiling or placed on movable bases, often linked by hinges like parodies of medieval polyptychs, the panels illustrate the artist's desire to liberate art from its conventional setting in a frame on a wall. Italian art historian Germano Celant writes: ‘With the Plurimi […] perceptions become enriched in the multiplication of visual and physical perspectives and, after throwing representation into crisis with spurious, intense signs, he reaches the point of demolishing the unity of the painting’s perimeter, disordering its existence to propagate the violence of creative disunity in all places’. Neither a sculpture nor a painting, but rather a hybrid of the two, Vedova dissolves the conventional form of panel painting. He collapses the distinctions between the materials of art-making and ordinary things; between painting and sculpture; and between the realms of art and everyday life.

Produced in the same year as Absurdes Berliner Tagebuch ’64, Bianco e nero embodies Vedova’s recourse to abstraction as a means to communicate his political leanings and aspirations. The composition is conflicted, angular, sharp and contrasted. It is a point of rupture.

From the same artist

More artists from the following country:

Italy

- Valerio ADAMI

- Yasmin BRANDOLINI D'ADDA

- Bruno CASSINARI

- Maurilio CATALANO

- Fabrizio CLERICI

- Pietro CONSAGRA

- Armando DE STEFANO

- Marta DELL’ANGELO

- Paolo della BELLA

- Tano FESTA

- Giosetta FIORONI

- Salvatore FIUME

- Carlo GUARIENTI

- Piero GUCCIONE

- Marcello JORI

- Dieter KOPP

- Jannis KOUNELLIS

- Leonardi LEONCILLO

- Luigi MAINOLFI

- Marina MARCOLIN

- Antonio MÁRO

- Franco MARROCCO

- Titina MASELLI

- Denise MASTEL

- Martina MERLINI

- Vasco MONTECCHI

- Luigi MORMINO

- NUNZIO

- Luigi ONTANI

- Mimmo PALADINO

- Giulio PAOLINI

- Gianfranco PARDI

- Enrico PAULUCCI

- Carlo PIZZICHINI

- Arnaldo POMODORO

- Carol RAMA

- Nino RUJU

- Giuseppe SALVATORI

- SALVO

- Aligi SASSU

- Mario SCHIFANO

- Emilio TADINI

- Nani TEDESCHI

- Marco TIRELLI

- Giulio TURCATO

- John VASSAR HOUSE

- Emilio VEDOVA

- Gianni VISENTIN

- Rodolfo ZILLI