4. Risks and dangers for democracy

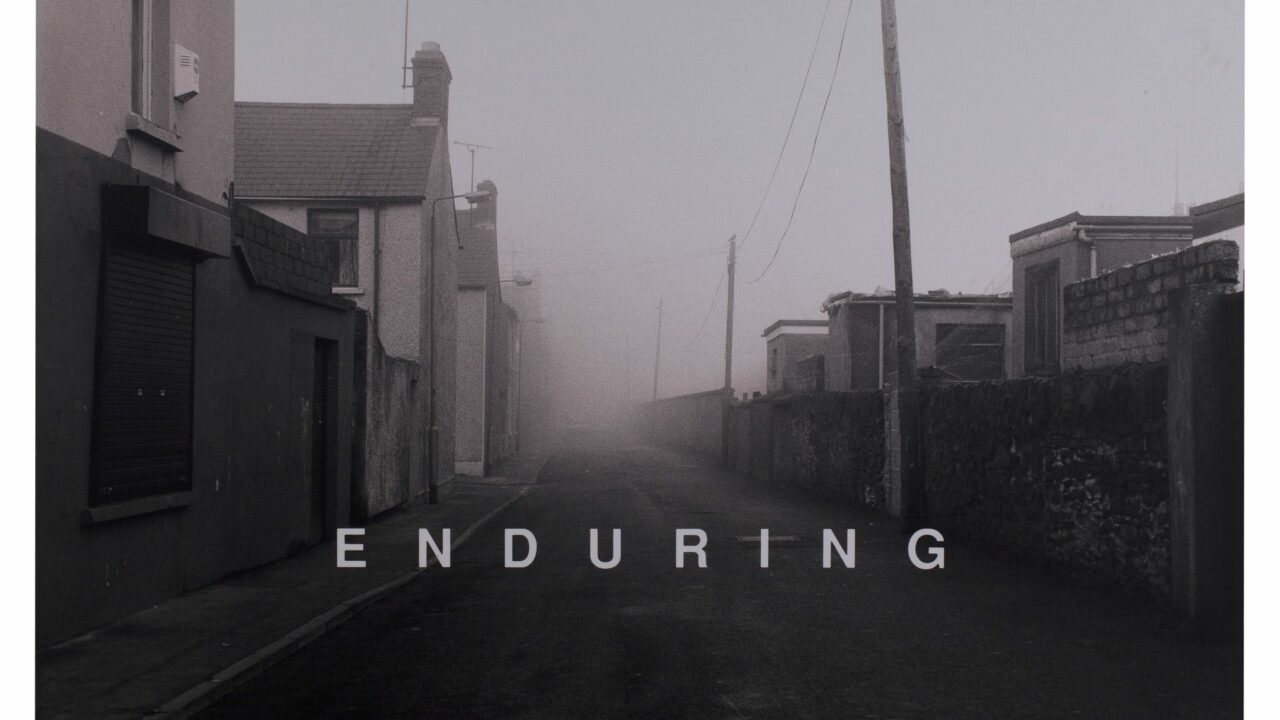

Polarization of conflicts and disagreements between different communities, fear of the future and excessive surveillance and control of individuals, are themes and concerns reflected in a series of works that echo states of crisis and unease, spurring us to adopt a conscious stance vis-à-vis the realities they interpret. Willie Doherty photographed an urban landscape, a desolate street in his native Derry shrouded in a luminous haze; the inhabitants, absent or locked up in their houses. Using an ellipsis, he captures a situation marked by hidden violence and tension, and labels it with the word Enduring – which denotes resistance, tenacity, integrity.

Artworks

Willie DOHERTY: Enduring, Derry, 1992 – On display in Parlamentarium, Brussels

TWO/FOUR/TWO (Art Group Created In 1996) Costas Mantzalos (*1963) & Constantinos Kounnis (*1973): Believe In Me, 2005 – On display in Parlamentarium, Brussels

James HANLEY :The Convert, 1992 – On display in Parlamentarium, Brussels

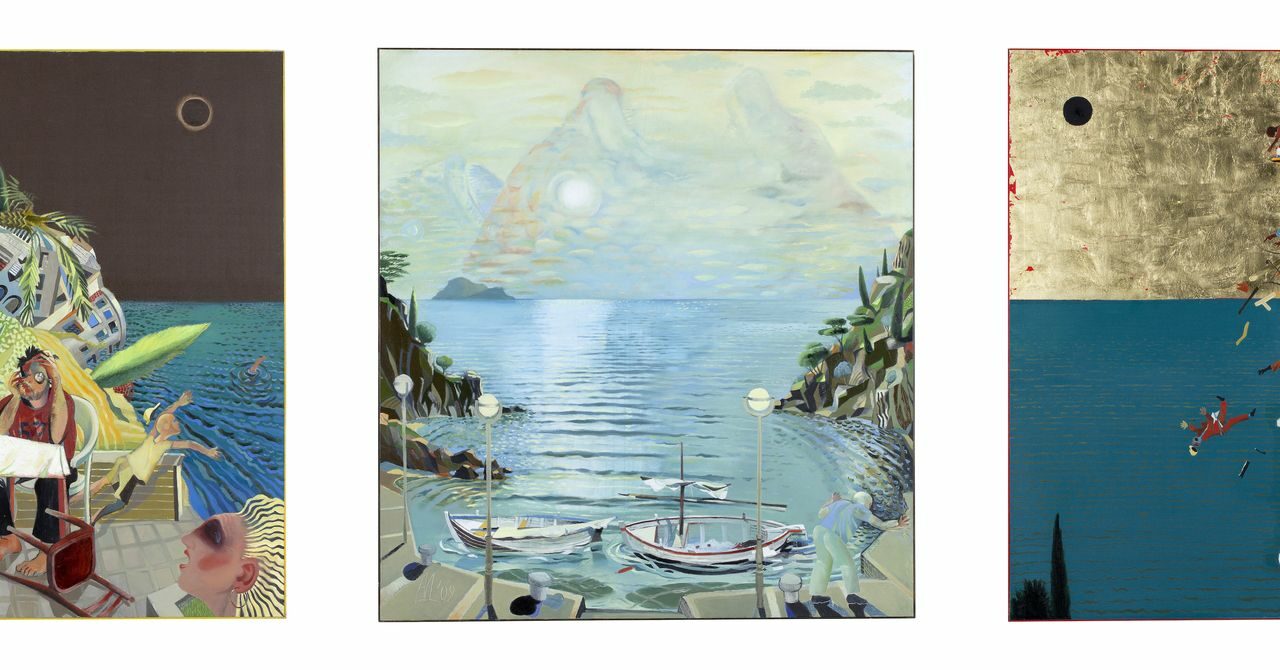

Andrey DANIEL : Trilogy: the Elusive Meaning of Cause and Effect, To Bruegel; the Mating Season of the Leviathans; the Death of the Worker X, 2009 – On display in Visitors’ area, Brussels

Flo KASEARU: Fears of a Museum Director, 2014 – On display in Parlamentarium, Brussels

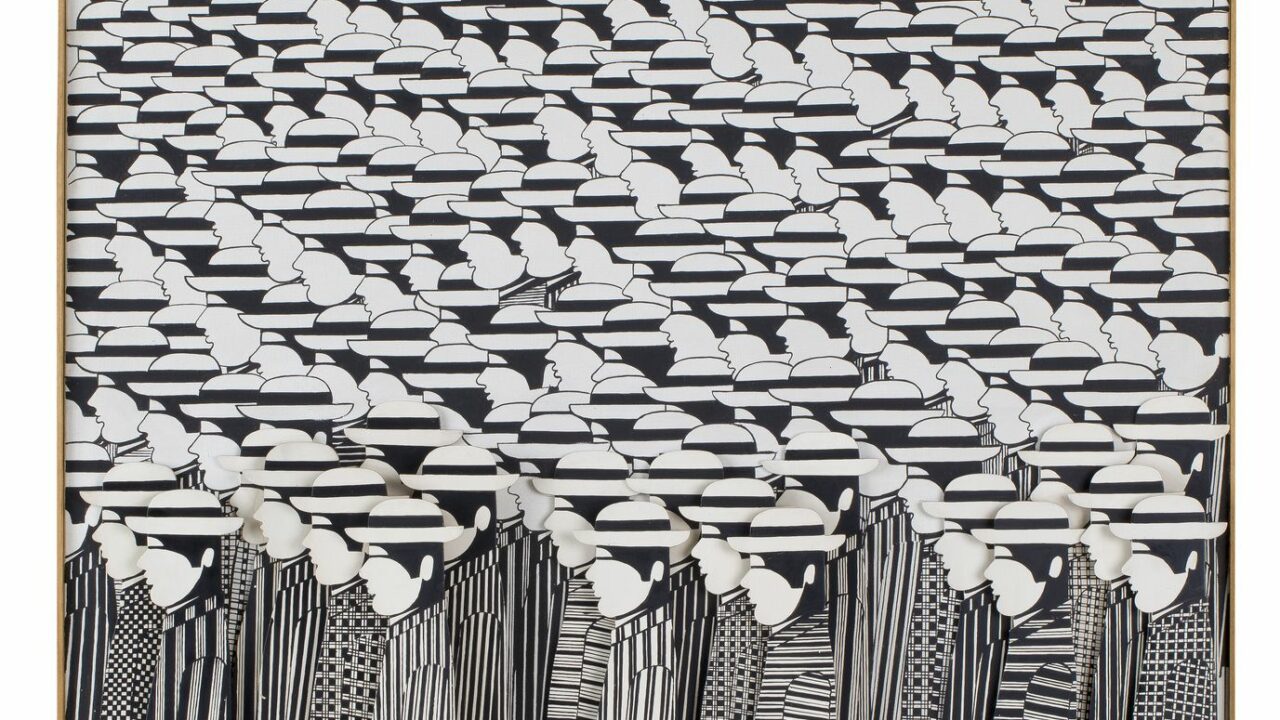

Yannis GAÏTIS : The Parade, 1983 – On display in Parlamentarium, Brussels

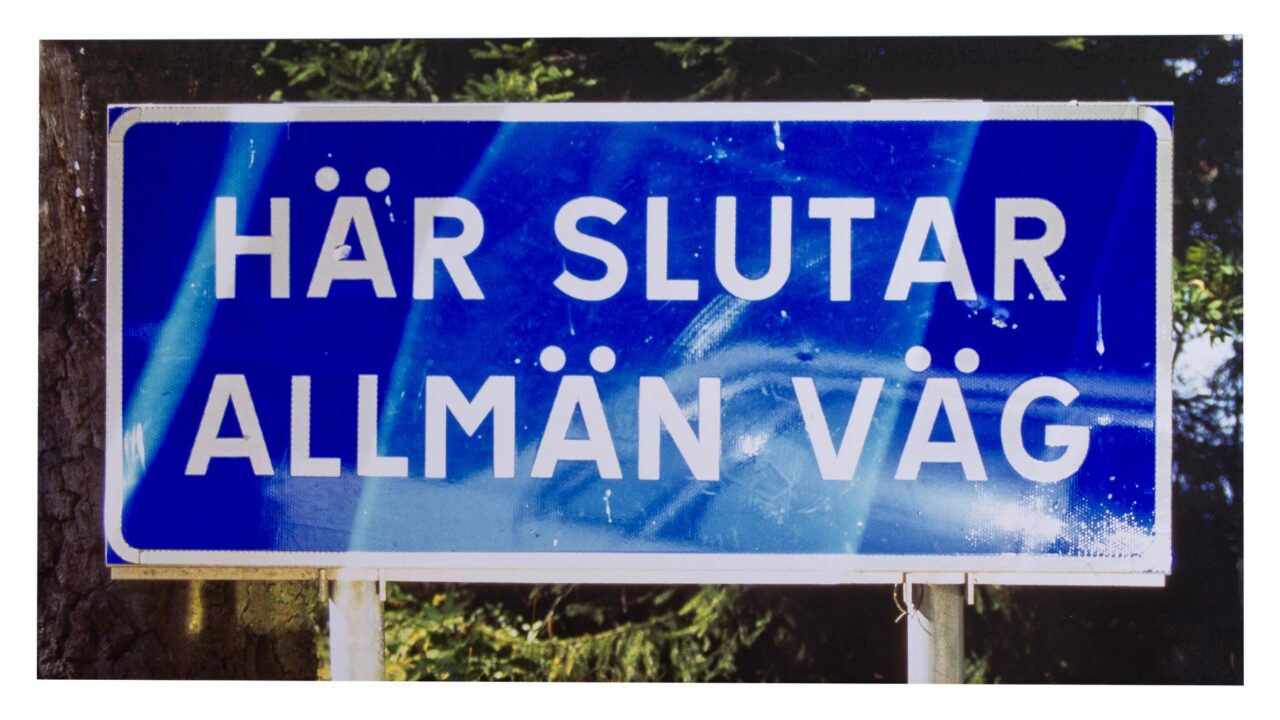

Dan WOLGERS : End of Public Road III, 1995 – On display in Visitors’ area, Brussels

Doherty thus resorts to a link between the word and the image, which had already been practiced in the 20th century by Dadaism, Surrealism and later on by Conceptual Art. He uses this semantic resource in reference to the historical, political and social conflict experienced in Northern Ireland, and alludes to the messages and graffiti written on the Derry walls by both sides facing each other.

These are laconic and, at first glance, enigmatic messages, such as those written on the diptych: Many have eyes but cannot see (1992). On the left and right wings the words: “Blind spot” and “Vanishing point” perhaps allude to the dead, blind spots which surveillance, whether through cameras or patrols, does not reach.

The eye that has the potential to see and inadvertently scrutinize certain areas of the territory and of social life, constitutes a disturbing iconographic element in the retro-illuminated photographic piece of the duo TwoFourTwo – Believe in me (2005), where the great eyelid of a human eye stands out behind a metal grid similar to the bars of a prison. Drawing on a specific historical-social context, Doherty has created an image – Endurance – whose meaning, if we disregard its geographical and political background, could be generically extrapolated to any other places and situations where civil society maintains a supportive, silent resistance in the face of a threat. In addition, Doherty’s work involves the will to keep alive the memory of the events that led to the conflict. From them, a warning can be drawn about the need to increase the civic and creative capacity of societies to peacefully solve problems, promote cooperation and avoid extreme, violent situations like the one depicted in James Hanley’s The Convert (1992).

When the State is transformed into a fearsome apparatus that does not serve the citizens but uses them and invades their privacy, then it takes on the monstrous form of a mythological Leviathan. This can be seen, emerging from the ocean, in the central panel of Andrey Daniel‘s Apocalyptic Triptych: Trilogy: The Elusive Meaning of Cause and Effect: To Bruegel, The Mating Season of the Leviathans, The Death of Worker X (2009). Thomas Hobbes’Leviathan (1651) by means of an homage to the sixteenth century painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder, is likely referenced by Daniel. Specifically, he would be referring to one of Brueghel’s masterpieces: Dulle Griet (ca. 1564) – Collection of the Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp -, in which the main character, Dulle Griet, is looking at the mouth of hell, personified as a leviathan face.

In the same way that Brueghel’s paintings could be seen in the 16th century as visual documents of popular culture, the characters in Daniel’s triptych are ordinary people of the 21st century: tourists on the left panel, construction workers on the right; all of them suddenly suffering a cosmic upheaval that severely disrupts their lives. In Bulgaria, Daniel was acknowledged as “an artist, a community leader, a colleague, a mentor, he established himself as one of the leading figures in art pushing Bulgarian painting forward at the close of the 20th and the turn of the 21st centuries”. As one of the best connoisseurs of the painter’s work has pointed out, Daniel claimed and believed that artists should synthesise meaning: “And if we do not learn to invent meaning, to synthesise meaning for ourselves and for others, for very large groups of people, then this existence will rather be some sort of vegetating”.

Other dangers and disasters – terrorism, war, vandalism, etc. – which also threaten democracy and freedom, have been humorously depicted by Flo Kasearu in the series of drawings Fears of a Museum Director (2014). These seemingly comical scenes take on a deeper significance: they express the fear of an uncertain future through an approach typical of journalistic cartoons, by displaying a repertoire of extreme and catastrophic situations in which any public or private institution could be involved.

The risk of non-critical thinking and alienation finds an accurate allegorical representation in the oil on wood by Yannis Gaitis: The Parade (1983). Here, the principles of overcrowding, indoctrination andhomogenisation have been portrayed, showingthe commonality of man transformed into a linear andalienated flock of identical human beings standingin overlapping rows. Gaitis lends a touch of humour to this rigid crowd of individuals, enabling us to more easily digest this representation of a social system that is overwhelmingly uniform. Eventually, a feeling of uncertainty is prompted by Dan Wolgers’ End of the public road (1995), where the viewer can recognize itself in the driver of the vehicle reflected in the metallic blue signage placed at the edge of the road. If we take the public road as a metaphorical image of civilization and the rule of law, we can then consider this photo as an ambiguous warning about what can be glimpsed beyond the scope where the principle of legal certainty rules.